Library programming up to about 2019 or so had a fairly familiar rhythm to it, with responsible adults putting on programs where they would guide children or teenagers through a well-defined process to create some form of a concrete end product, whether that was an art, a craft, or a digital object of some form.

Because of the concreteness of both the process and the product, this allowed the respectable adult presenter to practice their instruction and methods and troubleshoot some of the trickier parts of the process so that when their attendees ran into those same problems while trying to replicate the product, they could be gently guided through how to make it possible or given a new item to start over with so they could avoid the common pitfall they'd landed in. With such a constrained scope of possibilities to work with, the program also kept itself relatively self-contained, with the possibility of expansions and additional ideas left as an exercise for the attendee to go through on their own time, outside of the program, possibly using some of the handy print resources that are on display in the program room or the library, so there's a smooth transition from the hands-on portion into the books and reading portion, because that is, after all, right in the pocket of the library mission to put books in the hands of the curious.

Self-contained programs also work on the practical level, because a lot of public libraries don't have kids who can commit to a six-week program and guarantee that they'll appear every time. So, when the audience isn't guaranteed, keeping to kits, crats, robot boxes, and other well-defined, well-scoped itsems guarantees that both the presenter will appear knowledgeable and the attendees will have a successful and positive experience at the library.

Some kids, of course, don't understand that they're there to do the craft and then go out into the library and read books to satisfy any curiosity they might have about the subject. They do things like ask questions of the presenter or ask what other or alternative ways might be possible, or they think of a completely new idea and want to know how they might go about doing it. For a presenter that's only trained on the specific thing in the kit and not a wider understanding of the concepts or the alternatives (sometimes because they don't have time to get invested in a thing, other times because they're doing a program but it's not something they're very passionate about), a curious child sparks the danger alarm. Even with the idea of "I don't know, let's find out," there's still a certain amount of competence and expertise expected from the presenter when confronted with someone who wants to do something new. Getting out of your depth often leads to panic and anxiety, especially when they expect you to know All The Things.

At this point, I need to pause and explain that there's a difference between the deliberate presentation of yourself as a silly being that does wrong things because it's a hook for the kids to tell you that you're wrong and to help you do something the right way. Deliberate Silly is putting a pair of jeans on your head to ask kids whether or not that's the place where jeans go. You know it isn't, they know it isn't, but the point is to get them to shout "NO!" and tell you where the jeans do go. It's knowing that you're going to have a difficult time getting teens to pay attention to your boring presentation about school resources, so you instead pepper the slides and the presentation with memes (often old memes) just so that they'll pay attention (even if it is to comment that all of your memes are old). Deliberate Silly is doing those things intentionally, often with a wink.

The other kind of embarrassing thing, of not knowing, of looking stupid in front of the attendees, or peers, or otherwise, that's the kind that causes anxiety and worries about whether or not a program is being done "right" or "correctly". Because sometimes you tried your best and it looks nothing like what it's supposed to, even after all of that practice you put into it. Enough of that anxiety might mean swearing off programs or entire classes of programs because the anxiety of not being good enough at it or not being a big enough expert at it is terrifying and we are afraid of looking bad in front of kids and their grownups.

Naturally, in 2019, our Science Librarian debuted for us the Mobile Maker Cart, a cart full of supplies, parts, and pieces, with an accompanying binder of challenges and ideas for what to try in programming with those parts and pieces. Along with the materials, the Science Librarian offered trainings at community of practice meetings and other materials to give us examples of what we could do with the materials inside the kits. The idea was to make us comfortable with using the materials in the kit and to have an attempt or two at trying to achieve the goals detailed in the various programs.

Rather than provide detailed instructions on how to achieve those goals, however, the sheets in the binder gave us materials, goals to try, and a couple of pieces of information about the underlying concepts involved that we could use as hints to help steer the participants in directions that might work. Instead of a procedure list to follow with the guarantees of success, there were goals and it was up to us and the participants to figure out how we might use the materials to get to those goals. Failure was extremely likely. In fact, failure might be the only thing that happened throughout the entire program time. The Science Librarian assured us that it was okay to have a program where everyone failed at the goal, because the point of the programs was to go through the process of scientific thinking, experimenting, and iteration, rather than to replicate directions to create a finished product. Naturally, everyone was highly suspicious of this idea and worried that the kids and grownups alike might think the program poorly designed or that they ould stop seeing the library and its programming as a place to go. We were already nervous about having just squeaked by a funding vote, and now someone was telling us that it was okay to put on programs where kids might fail and have frustration at continuing to fail? That seemed like a huge risk to take in that environment.

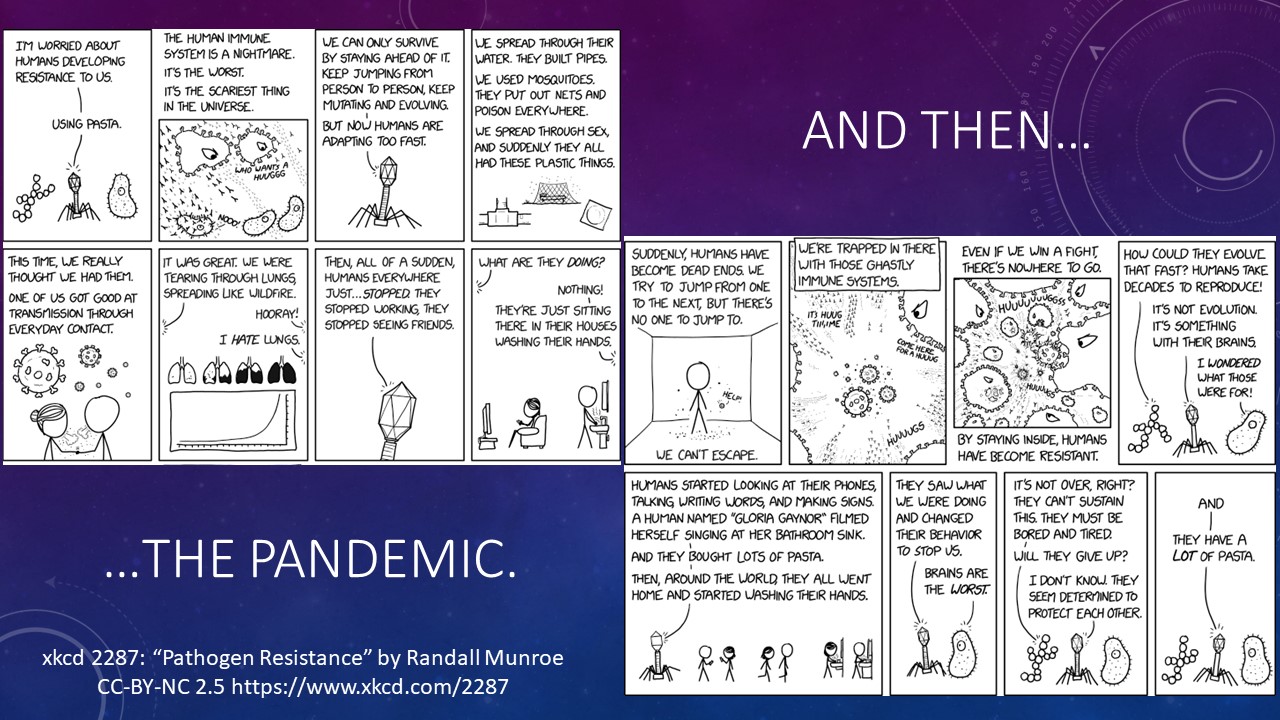

And then, well, COVID-19. Sudedenly, we weren't doing Mobile Maker Programming in our locations any more. In fact, we weren't doing any programming in our locations any more. All of that potential for failure at not knowing, or at things not turning out correctly, or not having the necessary expertise to make something happen, that all went to the virtual rooms instead! All of those anxieties came with some opportunities to practice some skills that I had tried when I was a kid and hadn't had great successes with. Like arts and crafts. What could possibly go wrong by changing from "looking like a dork in front of a room full of children" to "looking like a dork in front of a virtual room full of children?"